A Brief History of Modern Food Standards

Throughout human history, societies have developed standards to address several distinct, but related problems with the fruits of agricultural labor. Even in ancient societies, food and agricultural products needed to be prepared, packaged, or stored in certain ways to preserve freshness or prevent spoilage after harvest (Borrelli and Scazzosi 2020). This became even more important in the early modern period, when cash crops such as sugar or cotton were grown for the express purpose of trade with colonial powers (Beckert 2014; Mintz 1986; Singerman 2015). Purchasers were always alert to the possibility of fraud or misrepresentation, especially with luxury imports from colonial holdings, such as spices or tea (Hellyer 2021).

Most contemporary food standards can be traced to the rules and regulations that were developed in response to societal changes that occurred during the late nineteenth century (the 1800s) (Smith‐Howard 2022; Young 2014). As individuals left the countryside for better employment prospects in industrial cities, they were separated from the process of growing and producing food. It became necessary for farmers and food processors to communicate with consumers in distant urban markets (Cronon 1992; Rodgers 2001). The farmers and food processors used print advertising and marketing to convey their products’ superior quality or unique characteristics (Black 2023; Strasser 1989). However, without consistent standards or laws that regulate commercial speech, new food advertising only encouraged more fraud and deception (Balleisen 2017; Cohen 2019).

During the nineteenth century, food production and processing rapidly became industrialized (Chandler 1977; Levinson 2013). Innovations in transportation, such as refrigerated railcars, created national markets for perishable products such as meats (Specht 2019). At this time in the late 1800s, germ theory was still a relatively new concept. Although humans have always been aware that food can spoil, the precise cause of many foodborne illnesses and zoonotic diseases (diseases that spread between people and animals) was uncertain and was often attributed to “filth,” which referred to unsanitary conditions (Tomes 1999; Warner 1985).

Figure 10-1 shows a cartoonist mocking this uncertain food safety landscape. This image appeared on the cover of Puck, a mass-market magazine comparable to the Atlantic or Newsweek, in 1884. A man in professional attire is surrounded by a number of scientific instruments. He appears to be engaged in some complex scientific experiment because there is a chemistry book in his pocket. With closer examination, however, it looks as if this man is trying his best to enjoy a typical American breakfast. A milk-tester marks the presence of water to dilute the milk, a sand extractor is removing contaminants from the sugar, and a butter-tester is revealing the presence of hairs. Meanwhile, this man has placed his hash under a literal microscope — and is looking anxiously at what he found. This image poked fun at the poor state of food safety regulations in the 1880s. In the absence of meaningful public oversight, each person was forced to inspect their own food for safety and quality.

Although the Puck cartoon takes aim at common breakfast staples, meat products posed the most serious risks to consumers, workers, and animals in the late nineteenth century. Livestock diseases such as bovine tuberculosis, hog cholera, and Texas fever were widespread and eroded confidence in the American meat supply at home and in foreign markets (Anderson 2019; Booker 2018; Olmstead and Rhode 2015). In 1905, the journalist and muckraker Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, which described the horrible conditions in American meatpacking facilities in excruciating detail. Americans were more shocked by the descriptions of the unsanitary handling of meat carcasses than the dangerous working conditions that Sinclair sought to expose (Young 1985). The Jungle caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who championed “pure food” legislation the following year in the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act (Kolko 1963; Olmstead and Rhode 2015).

In 1938, the Pure Food and Drug Act was replaced by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), which established the modern US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as we know it today (Carpenter 2014). Although scientific understanding of food safety risks continued to improve over time, new developments raised new concerns such as pesticide and chemical residues in the food supply (Guthman 2019; Vogel 2013). Scientific breakthroughs, such as antibiotics, hormones, and new food and feed additives reduced some risks, while also creating entirely new challenges for the regulatory agencies (Marcus 1994; Landecker 2016; Smith-Howard 2017).

By the 1980s, Americans were in a similar quandary as their nineteenth-century counterparts who were concerned with “pure food.” On one hand, science and technology had improved dramatically during the twentieth century. Food inspection conducted by the FDA was based on microbiological and chemical sampling, and was supported through the enforcement of good manufacturing practices and periodic audits. Despite these advances, foodborne pathogens and chemical residues posed greater risks than ever from Alar (daminozide) in apples to E. Coli in beef (Nestle 2010).

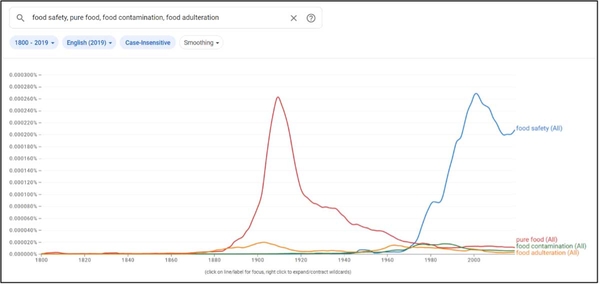

Food safety scares in the US and Europe during the early 1990s prompted dramatic policy changes that shaped food regulation today. One of the most significant changes was the development of process controls that addressed food safety, known as “Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points,” or HACCP. This was developed originally in the 1960s through a partnership with NASA and the Pillsbury Company to ensure the safety of food in space (“Happy 50th Birthday to HACCP: Retrospective and Prospective” 2012; Ross-Nazzal 2007). However, HACCP was not formally incorporated into US food regulations until the mid-1990s, when several children died from complications of eating undercooked hamburgers that were contaminated with E. Coli (Benedict 2013; Murano, Cross, and Riggs 2018). Later, HACCP was incorporated into the food laws of the newly formed European Union and the standards of the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an international body that facilitates global trade in food and agricultural products. The HACCP principles were also incorporated into a number of private standards and certification regimes developed by industry consortia in response to the new food safety risks – and legal liabilities – of the era. Today, most food safety standards around the world are based on HACCP principles, in which producers are evaluated primarily on the effectiveness of their processes to ensure safe food (Caswell and Hooker 1996; Merck 2020; Unnevehr and Jensen 1999). Thus, “food safety” may be a relatively new concept in the history of food and agriculture, but public concern about the safety and quality of food is certainly not new (Hurt 2022).

Strategies for Enforcement of Food Standards

Food standards are enforced by at least one of the following methods:

- Inspection

- Grading

- Audits/Certifications

| Inspection | Grading | Audits/Certifications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is involved | Examination to confirm that a product meets specific criteria (“wholesome”) for safety or quality. May involve different approaches depending on the product or agency. | Assessment of quality based on an ideal (such as US No. 1). Typically based on physical characteristics such as shape, size, and defects. | Evaluation of processes and procedures, usually done by a third party, with less emphasis on inspecting or sorting individual products. |

| Purpose | Exclude adulterated or misbranded products from the marketplace. Give inspectors the ability to condemn or recall products deemed unsafe. | Sort and differentiate marketable products based on quality. Higher grade confers price premium with retailers. | Communicate consistency or quality of processes to buyers or other partners in the supply chain. |

| For example | USDA or FDA inspection. | USDA grades. | FDA GMP audits, USDA GAP audits, GlobalGAP, BRC, SQF. |

| When | Since 1800s, updated in 1960s, 1990s. | At least since 1800s, with modern grades established in the 1920s. | Increased importance since 1980s/1990s. |

Types of Food Standards

Most food standards address one or more of the following types of problems:

Quality control: Standards that distinguish between comparable products based on an assessment of purity, refinement, value, or other pre-defined characteristics.

- Grades or other hierarchical classifications (Grade A, B, C, No. 1, 2). Qualitative classifications (“superfine, jumbo, fancy”) also refer to quality standards.

- Depending on the market demand, it may be difficult or impossible to sell foods that are determined to be low-grade (or “off-grade”). These foods may be used for other purposes such as canning or in processed foods.

- Quality can be an indicator of safety (a sweetpotato with no surface defects is less likely to rot), although in general, standards focused on quality control may not necessarily relate to safety.

- What some scholars call “social labeling,” such as non-GMO, hormone-free, or antibiotic-free, can also be considered quality standards, since these characteristics rarely have a direct impact on safety or health.

Anti-Fraud/Deception: Standards that ensure that a product is what it claims to be on the label.

- Food that is not labeled accurately can be deemed “misbranded” according to USDA and FDA regulations and can be removed from the marketplace.

- Some examples of food fraud or misbranding include false claims about the health benefits of certain ingredients, misleading or partially filled packaging, or attempts to misrepresent the color of food with dye or colored cellophane.

- Anti-fraud measures have been achieved historically through inspections and certifications, and are closely associated with quality control.

- Misbranding most frequently occurs today from errors in packaging and labeling, or the failure to declare common allergens, such as milk or wheat.

Health and/or Safety: Standards that distinguish between products that are safe to sell or consume (“wholesome”) and products that are unsafe or pose a risk to public health (“adulterated”).

- Health and safety inspections are the most common way that health and safety standards are enforced. Safety inspections may involve examinations of end products, facilities, processes, or all of the above.

- Labeling that notifies consumers of allergens (peanuts, tree nuts, phenylalanine, or sesame) are health and safety measures that warn individuals with life-threatening allergies about specific products or ingredients in processed food products (DeSoucey and Waggoner 2022).

- Some standards, such as livestock feed additives or animal welfare provisions, may have implications for animal health as well as human health.

- Informational labeling, such as Nutrition Facts, can indirectly address health concerns by communicating information that is relevant to consumers’ health in a neutral, fact-based way (Frohlich 2017).

Exports/Markets: Standards that relate to the ability of producers to access new or previously inaccessible markets.

- Standards in this category relate to efforts to improve domestic producers’ access to foreign markets (market access) or to standards that are focused on prohibiting certain foreign products from entering a given domestic market (protectionism).

- Countries that are signatories to the World Trade Organization agreements are not permitted legally to use laws, standards, or regulations to prevent free trade in food and agricultural products - but they do. Such trade barriers, called “technical barriers to trade,” can lead to trade disputes in the international court if left unresolved (Davis 2003).

- Private and international standards, such as SQF International, GlobalGAP, and BRC have helped to ease the impact of trade between countries with incompatible regulations. However, private standards can make it more difficult for farmers in the Global South (Africa, Latin America, parts of South Asia) to access those same markets due to the cost and complexity of compliance (Post 2005).

Key Food Standards in Postharvest

One way to distinguish the differences between the different food standards in use today is with the Figure 10-3. All potential standards fall on a continuum between public and private, voluntary and compulsory. This chart can help you distinguish between standards which are legally required and which are functionally required to sell your product in the marketplace.

NOTE: Consult with your local Extension agent or regulatory affairs officer at your company to ensure that you are complying with all rules and regulations, as well as any additional standards not listed here. This figure is illustrative of common standards, and is not exhaustive.

The following sections include brief descriptions of some important food standards to consider in postharvest engineering.

Good Manufacturing Practices

Good manufacturing practices (GMPs) refers to a set of regulations developed by the US Food and Drug Administration that outline requirements for methods, equipment, facilities, and production and process controls that ensure food safety. Food produced in environments that do not comply with GMPs may be considered adulterated. The “general” GMPs were developed in the late 1960s, and were revised in 2015 to reflect overall changes to the food safety system in the Food Safety Modernization Act.

The FDA promulgates “general” GMPs, as well as some GMPs that are specific to certain types of food, such as supplements, low-acid canned foods, and infant formula. Since the GMPs are more closely associated with food manufacturing or processing, raw agricultural commodities are typically exempted from GMP requirements.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP)

HACCP (pronounced “hassip”) is “a system which identifies, evaluates, and controls hazards which are significant for food safety.” The HACCP system has seven core processes (Codex Alimentarius Commission 2003):

- Conduct a hazard analysis and identify control measures. A food safety hazard is any biological, chemical, or physical property that may cause a food to be unsafe for human consumption.

- Determine the critical control points. A critical control point (CCP) is a point, step, or procedure in a food manufacturing process at which control can be applied and, as a result, a food safety hazard can be prevented, eliminated, or reduced to an acceptable level.

- Establish validated critical limits (for each critical control point.) A critical limit is the maximum or minimum value to which a physical, biological, or chemical hazard must be controlled at a critical control point to prevent, eliminate, or reduce the hazard to an acceptable level.

- Establish a system to monitor control of CCPs. In the United States, it is required that each monitoring procedure and its frequency are listed in the HACCP plan.

- Establish the corrective actions to be taken. Corrective actions are intended to ensure that no product injurious to health or otherwise adulterated as a result of the deviation enters commerce.

- Validate the HACCP plan and then establish procedures for verification to confirm that the HACCP system is working as intended.

- Establish documentation of all procedures and records appropriate to these principles and their application. The HACCP regulations require that all manufacturing plants maintain a written HACCP plan and records that document the monitoring of critical control points, critical limits, verification activities, and the handling of processing deviations.

The HACCP system can be applied at all stages of a food chain from the farm until it reaches the consumer. The US Department of Agriculture regulates meat, poultry, and farmed catfish HACCP systems (9 CFR part 417), while the US Food and Drug Administration regulates HACCP in seafood and juice (21 CFR part 120 and 123). Even where HACCP is not required, it is used as a “voluntary” system in many other contexts.

GAP (Good Agricultural Practices)

You are more likely to hear the term “GAP” in relation to USDA’s agricultural audits, but the term can refer to at least two different types of audits and certifications that reflect best practices in agriculture production and postharvest:

USDA GAP Audits: The USDA’s good agricultural practices (GAP) audits are voluntary audits that verify that fruits and vegetables are produced, packed, handled, and stored to minimize risks of microbial food safety hazards. The USDA performs several different types of GAP audits; the type depends on the customers’ request.

Global GAP Certification: GlobalGAP, which originated in Europe in 1997 as EUREPGAP, focused on certifying produce trade within the countries of the EU. In 2007, the organization changed its name to GlobalGAP to reflect the standards greater global reach and influence.

GLOBAL GAP Certification covers:

- Food safety and traceability

- Environment (including biodiversity)

- Workers’ health, safety, and welfare

- Animal welfare

- Integrated Crop Management (ICM), Integrated Pest Control (IPC), Quality Management System (QMS), and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP)

Traceability

Traceability refers to any system used by producers to track a product from its point of origin to a retail location where it is purchased by consumers. Traceability is often referred to as “farm to fork” in the EU or “traceback” in the US. Traceability systems provide information on the source, location, movement, and storage conditions of produce. The systems allow growers, packers, processors, and distributors to identify factors that affect quality and delivery. Traceability can also aid regulators and processors in the event of a recall to more precisely identify, locate, and recall affected products, and to address supply chain issues to prevent future recalls.

The US has been slower to adopt mandatory traceability provisions than other countries or economic areas. In 2002, a European Union food law established traceability requirements in the European Union. The Produce Traceability Initiative, which is an industry-led effort to enhance traceability throughout the entire produce supply chain, was established in 2008. However, it was not until 2022 that traceability was formally required under FDA’s Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), and it only applies to certain foods that have been deemed high-risk.

Traceability is incredibly important. Some of the key benefits include the following:

- Ability to determine the origin of a product, ingredient, or component.

- Protection of public health and safety.

- Limitation of losses.

- Lower costs.

In addition, traceability achieves the following:

- Simplifies problem-solving in the event of a defective or contaminated product, ingredient, or component.

- Allows issues to be more quickly identified, contained, and resolved.

- Builds trust and confidence in the supply chain.

- Verifies that produce is marketed accurately (such as locally grown).

- Improves operating efficiencies for growers, packers, and shippers.

Summary

Food standards are a critical part of postharvest engineering that address potential hazards in food safety and quality. Historically, ensuring the safety and quality of food involved direct inspection of individual products. Most food standards today focus on audits and certification of processes rather than inspection of end products. In postharvest, you will likely be held accountable to multiple standards that come from many sources, both public and private, as well as domestic and international. These standards may even overlap or conflict with one another, and it may be your job to sort through them to identify which are the most important for your company. Most food standards in use today are based on the seven principles of HACCP, which draw on engineering concepts of “modes of failure” and involve developing a plan to identify hazards and reduce risks. Improving traceability and responding quickly to recalls are important because both benefit the industry as well as consumers.

Additional Resources

Standards Organizations

Produce Traceability Initiative

FDA

HACCP Principles (1997)

HACCP at FDA (Dairy, seafood, juice, retail)

FDA History – 80 Years of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

USDA

NC State Extension

UC Davis Postharvest Center

References

Anderson, J. L. 2019. Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press. ↲

Balleisen, Edward J. 2017. Fraud: An American History from Barnum to Madoff. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↲

Beckert, Sven. 2014. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ↲

Benedict, Jeff. 2013. Poisoned: The True Story of the Deadly E. Coli Outbreak That Changed the Way Americans Eat. New York: February Books. ↲

Black, Jennifer. 2023. Branding Trust: Advertising and Trademarks in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press. ↲

Booker, Matthew. 2018. “Before The Jungle : The Atlantic Origins of US Food Safety Regulation.” Global Environment 11 (1): 12–35. ↲

Borrelli, Noemi, and Giulia Scazzosi. 2020. After the Harvest: Storage Practices and Food Processing in Bronze Age Mesopotamia. Turnhout: Brepols. ↲

Carpenter, Daniel. 2014. Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↲

Caswell, Julie A., and Neal H. Hooker. 1996. “HACCP as an International Trade Standard.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 78 (3): 775–79. ↲

Chandler, Alfred D. 1977. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ↲

Codex Alimentarius Commission. 2003. General Principles of Food Hygiene, CAC/RCP 1-1969. ↲

Cohen, Benjamin R. 2019. Pure Adulteration: Cheating on Nature in the Age of Manufactured Food. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. ↲

Cronon, William. 1992. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton. ↲

Davis, Christina L. 2003. Food Fights over Free Trade: How International Institutions Promote Agricultural Trade Liberalization. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↲

DeSoucey, Michaela, and Miranda R. Waggoner. 2022. “Another Person’s Peril: Peanut Allergy, Risk Perceptions, and Responsible Sociality.” American Sociological Review 87 (1): 50–79. ↲

Frohlich, Xaq. 2017. “The Informational Turn in Food Politics: The US FDA’s Nutrition Label as Information Infrastructure.” Social Studies of Science 47 (2): 145–71. ↲

Guthman, Julie. 2019. Wilted: Pathogens, Chemicals, and the Fragile Future of the Strawberry Industry. Berkeley: University of California Press. ↲

“Happy 50th Birthday to HACCP: Retrospective and Prospective.” 2012. Food Safety Magazine. November 26, 2012. ↲

Hellyer, Robert I. 2021. Green with Milk and Sugar: When Japan Filled America’s Tea Cups. New York: Columbia University Press. ↲

Hurt, R. Douglas. 2022. A Companion to American Agricultural History. Wiley Blackwell Companions to American History. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ↲

Kolko, Gabriel. 1963. The Triumph of Conservatism: A Re-Interpretation of American History. The Free Press. ↲

Landecker, Hannah. 2016. “Antibiotic Resistance and the Biology of History.” Body & Society 22 (4): 19–52. ↲

Levinson, Marc. 2013. The Great A & P and the Struggle for Small Business in America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ↲

Marcus, Alan I. 1994. Cancer from Beef : DES, Federal Food Regulation, and Consumer Confidence. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↲

Merck, Ashton W. 2020. “The Fox Guarding the Henhouse: Coregulation and Consumer Protection in Food Safety, 1946-2002.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Durham: Duke University. ↲

Mintz, Sidney W. 1986. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books. ↲

Murano, Elsa A, H Russell Cross, and Penny K Riggs. 2018. “The Outbreak That Changed Meat and Poultry Inspection Systems Worldwide.” Animal Frontiers 8 (4): 4–8. ↲

Nestle, Marion. 2010. Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety. Updated and Expanded. Berkeley: University of California Press. ↲

Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul Webb Rhode. 2015. Arresting Contagion: Science, Policy, and Conflicts over Animal Disease Control. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↲

Post, Diahanna Lynch. 2005. “Food Fights: Who Shapes International Food Safety Standards and Who Uses Them?” Ph.D. Diss. University of California, Berkeley. ↲

Rodgers, Daniel T. 2001. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, London: Belknap. ↲

Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. 2007. “From Farm to Fork: How Space Food Standards Impacted the Food Industry and Changed Food Safety Standards.” Societal Impact of Spaceflight, NASA, Washington, 219–36. ↲

Singerman, David Roth. 2015. “Inventing Purity in the Atlantic Sugar World, 1860–1930.” Enterprise & Society 16 (4): 780–91. ↲

Smith-Howard, Kendra. 2017. “Healing Animals in an Antibiotic Age: Veterinary Drugs and the Professionalism Crisis, 1945–1970.” Technology and Culture 58 (3): 722–48. ↲

———. 2022. “Consumers, Producers, and the Shifting Logic of Food Safety.” In A Companion to American Agricultural History, edited by R. Douglas Hurt, 1st ed., 327–40. Wiley.

Specht, Joshua. 2019. Red Meat Republic : A Hoof-to-Table History of How Beef Changed America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↲

Strasser, Susan. 1989. Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the American Mass Market. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books. ↲

Tomes, Nancy. 1999. The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. ↲

Unnevehr, Laurian J, and Helen H Jensen. 1999. “The Economic Implications of Using HACCP as a Food Safety Regulatory Standard.” Food Policy 24 (6): 625–35. ↲

Vogel, Sarah A. 2013. Is It Safe? BPA and the Struggle to Define the Safety of Chemicals. Berkeley: University of California Press. ↲

Warner, Margaret. 1985. “Hunting the Yellow Fever Germ: The Principle and Practice of Etiological Proof in Late Nineteenth-Century America.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 59 (3): 361–82. ↲

Young, James Harvey. 1985. “The Pig That Fell Into The Privy: Upton Sinclair’s ‘The Jungle’ and the Meat Inspection Amendments of 1906.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 59 (4): 467–80. ↲

———. 2014. Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906. Princeton University Press.

Publication date: May 1, 2025

Other Publications in Introduction to the Postharvest Engineering for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables: A Practical Guide for Growers, Packers, Shippers, and Sellers

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Produce Cooling Basics

- Chapter 3a. Forced-Air Cooling

- Chapter 3b. Hydrocooling

- Chapter 3c. Cooling with Ice

- Chapter 3d. Vacuum Cooling

- Chapter 3e. Room Cooling

- Chapter 4. Review of Refrigeration

- Chapter 5. Refrigeration Load

- Chapter 6. Fans and Ventilation

- Chapter 7. The Postharvest Building

- Chapter 8. Harvesting and Handling Fresh Produce

- Chapter 9. Produce Packaging

- Chapter 10. Food Safety and Quality Standards in Postharvest

- Chapter 11. Food Safety

- Postscript — Data Collection and Analysis

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.